A Snapshot of the Past

Looking back in time might sound straight out of a science-fiction or fantasy novel, but in Astronomy, all one has to do is look up (with equipment that cost billions to make). This is because space is huge — whatever size you think it is, it’s still too small. As a result, light must take an unimaginably long journey to get from a faraway object to us. As it travels, space expands, stretching the light waves; the light has been redshifted.

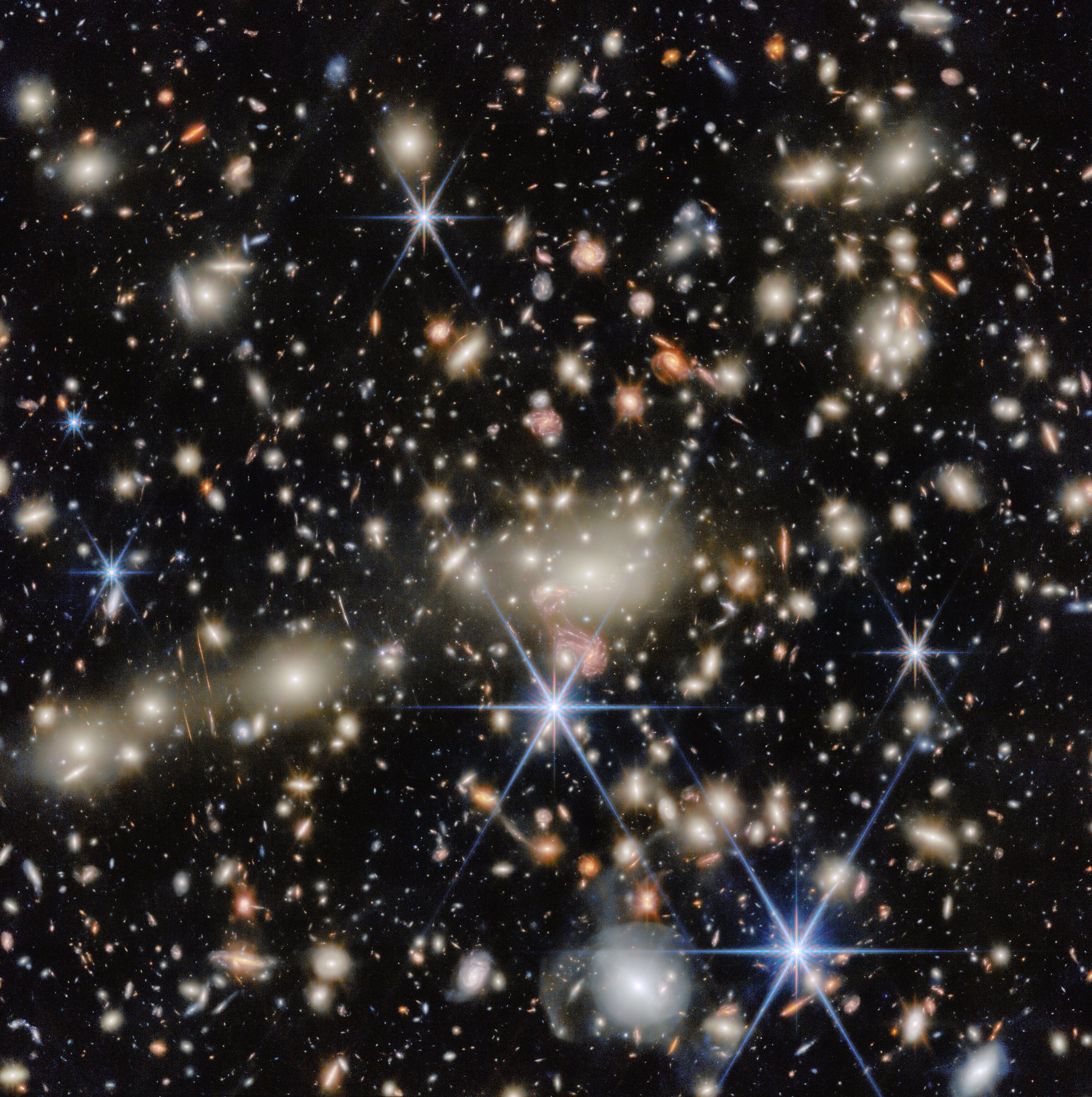

This was what made the James Webb Space Telescope so revolutionary.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Northrop Grumman

JWST was built to detect severely redshifted light, light that was emitted billions and billions of years ago, allowing astronomers to look further into the past than ever before. And, billions and billions of years ago, there were these small, red coloured objects.

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Dale Kocevski (Colby College)

They can be found in any direction, too small to be properly resolved even by JWST. No one knew what these objects were, only that they were around when the Universe was young, only 600 million years to 1.5 billion years (The universe is currently about 13.8 billion years old). For their appearance, they were given a cute, catchy name: Little Red Dots (LRDs).

It is important to note that these little red dots are, in fact, little and red, not just really far. They have a radius of about 2% that of our Milky Way galaxy, and are red even after adjusting for redshift.

Mysterious Red Dots

The true nature of LRDs is still up for debate. The curious properties of LRDs have led to many competing theories as to what they could be.

Stars, lots of them

The stars-only hypothesis posits that LRDs are galaxies of red stars. However, it quickly became unpopular. To resemble LRDs as they are observed, these galaxies would require approximately the same number of stars as the Milky Way, compacted to a fraction of its size. This would make them an entire order of magnitude denser than globular star clusters! Not only would this be unstable, but there also would not have been enough time to form that many mature stars so early into the evolution of the Universe. The stars we see in globular star clusters are billions of years old themselves.

Image credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, A. Sarajedini, G. Piotto, M. Libralato

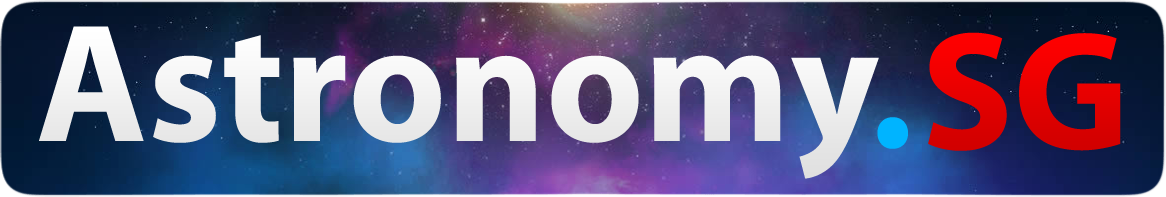

Black Holes, Red Covers

The leading hypothesis for LRDs is that they are supermassive black holes (SMBHs), similar to those found in the centre of galaxies. They’re early examples of Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs) — SMBHs at the centres of galaxies, which are incredibly bright and energetic. Analyses of the light emitted from LRDs show close correlation with that of SMBHs, but are not entirely similar.

Image credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser and L. Calçada

AGNs produce massive amounts of X-Rays and radio waves, and LRDs do not. AGNs also make up a small portion of the entire galaxy’s mass, while the black holes within LRDs (if they do exist) would take up a large majority of the total mass of the object.

The lack of X-ray and radio-wave radiation has been resolved in a recent paper. LRDs could be black holes cocooned in a cloud of dense ionised gas, which would absorb the various radiation types and reemit them in the optical spectrum.

Image credit: MPIA/HdA/T. Müller/A. de Graaff

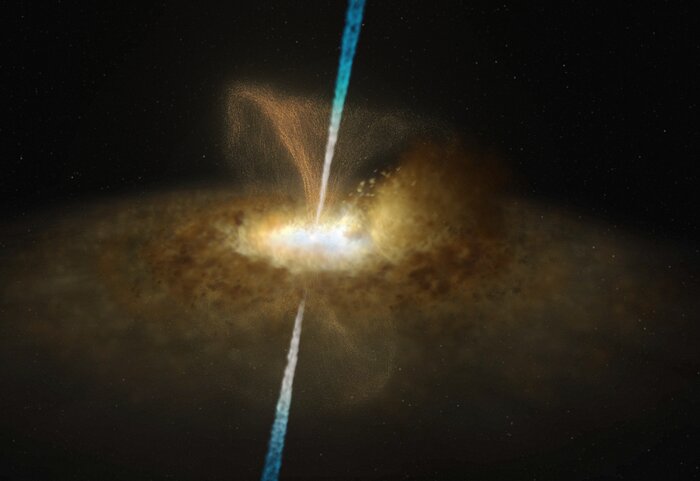

Stars, but Big

Another theory is that they are supermassive primordial stars.

Stars can be categorised into populations based on when they formed. The early Universe is made up of mostly Hydrogen and Helium, with heavier elements (referred to as ‘metals’ in Astronomy) only appearing later after being formed in the cores of stars. Therefore, stars formed earlier would have lower metal content, or metallicity, than stars formed recently.

Our sun (with a metallicity of 1.4%) is part of the latest group of stars, the Population I stars with high metallicity. Population II stars are older, have lower metallicities, and are typically more than 10 billion years old. Population III stars remain a purely hypothetical class of stars, yet identified, and would have little to no contamination of metals.

Astronomers have modelled supermassive Population III stars and found that they match closely with features of LRDs. These stars would have to be incredibly massive, however, about a million times the mass of the sun. To put that into perspective, the most massive star we know is only about 290 solar masses.

Image credit: CfA/Melissa Weiss

These supermassive stars could also be the progenitors — what came before — supermassive black holes that we see today.

This theory has the advantage of being relatively simple compared to the SMBH hypothesis, which requires more components to properly match observations of LRDs. However, the required formation rate of these supermassive stars would be in the upper limits of current evolution models of the Universe.

Baby Pictures

JWST has allowed astronomers to look back in time, way back into the Universe’s infancy, in hopes of clarifying theories and questions surrounding the very beginnings of existence. However, it appears that this gave us more questions than answers. In a way, it is like seeing photos of your parents as babies.

Image credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, C. Willott (National Research Council Canada), R. Tripodi (INAF – Astronomical Observatory of Rome)

Written by Chloe Lim 31 January 2026

References

Cranfill, S., & Team, N. W. M. (2025, August 28). Newfound Galaxy Class May Indicate Early Black Hole Growth, Webb Finds – NASA Science. NASA Science. https://science.nasa.gov/missions/webb/newfound-galaxy-class-may-indicate-early-black-hole-growth-webb-finds/

Pacucci, F. (2024, September 8). Hidden, compact galaxies in the distant universe—searching for the secrets behind the little red dots. phys.org. Retrieved January 30, 2026, from https://phys.org/news/2024-09-hidden-compact-galaxies-distant-universe.html

Bakich, M. E. (2026, January 7). How did early black holes form? Astronomy Magazine. https://www.astronomy.com/science/how-did-early-black-holes-form/

Guia, C. A., Pacucci, F., & Kocevski, D. D. (2024). Sizes and Stellar Masses of the Little Red Dots Imply Immense Stellar Densities. Research Notes of the AAS, 8(8), 207. https://doi.org/10.3847/2515-5172/ad7262

Guia, C. A., Pacucci, F., & Kocevski, D. D. (2024). Sizes and Stellar Masses of the Little Red Dots Imply Immense Stellar Densities. Research Notes of the AAS, 8(8), 207. https://doi.org/10.3847/2515-5172/ad7262

Nandal, D., & Loeb, A. (2025). Supermassive stars match the spectral signatures of JWST’s little red Dots. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2507.12618