When one thinks of space, breathtaking images of colourful nebulae, starry skies, and beautiful planets come to mind. We are incredibly familiar with the visible light spectrum, and the many insights that visible light can give us, after all, it is how we see the world. The visible spectrum is, however, a fraction of the entire electromagnetic spectrum. Today we dive into microwaves, and a curious phenomenon known as masers.

The word ‘masers’ comes from an acronym – Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Sharper readers might notice its similarity to its far more ubiquitous variant: lasers (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation). It is essentially a laser but for microwave radiation instead of visible light. Like lasers, radiation in the form of microwaves is amplified or strengthened via stimulated emission. That previous sentence is basically a restating of the acronym, to understand the mechanics of masers, we would need to take a brief detour into quantum mechanics.

Energy levels and photon emission

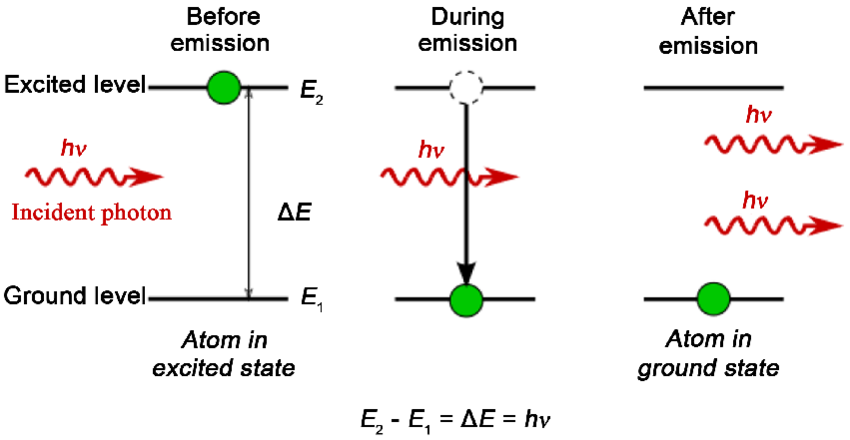

Atoms and molecules are quantum mechanical systems with different energy states. Think rungs of a ladder. When an atom or molecule at a higher energy state, or an excited state, transitions to a lower energy state, it will emit the energy lost in the form of a photon. Energy levels are constant and discrete for each species of atom or molecule, so energy changes are also fixed. Therefore, transitions from an excited state to a lower state in a particular molecule would always result with energy loss of the same amount. The energy of a photon is directly proportional to its frequency, so only photons of a specific frequency would be emitted for a specific state transition. The opposite can happen too, where a photon is absorbed by an atom or molecule, which transitions from a lower state to a higher state.

Emissions due to a transition from a higher energy state to a lower one usually happens spontaneously, hence the name ‘Spontaneous Emission’ used to describe such a process. However, there are Stimulated Emissions, in which a photon of that specific frequency passes by an atom or molecule in the excited state, triggering a transition into a lower energy state. A photon of the same frequency as the trigger is released, resulting in two photons of the same frequency. Those two photons can then trigger two other excited atoms or molecules, resulting in a chain reaction where exponentially more photons are emitted. Therefore in suitable masing conditions, a dim source of photons can be amplified into an intense beam: a maser/laser.

Several conditions are required for this to work. Due to absorption, if the majority of the population of atoms or molecules are at the lower energy state, photons emitted would simply be absorbed. Therefore, a majority of the population has to be in an excited state (known as population inversion), which is rare as particles dislike being excited. An outside source of energy is needed to maintain a population inversion, known as a ‘pumping mechanism’, to pump the population with energy. The photons involved would have frequencies in the visible spectrum and microwave spectrum for lasers and masers respectively. Maser activity can be seen in strong spikes at certain microwave frequencies in the spectra of an object.

In Space

Masers are special because, unlike lasers, they are naturally occurring. The universe contains many natural phenomena that can serve as pumping mechanisms to cause population inversion within nearby molecular clouds, transforming them into suitable amplifying mediums for microwaves, i.e. masers.

Astrophysical masers are bright. If assumed to be a blackbody, the effective temperature of some masers might work out to be many times hotter than the core of the sun (not the surface, the core!). The microwave radiation of masers is so intense that the first was actually discovered back in the 1960s, before lasers were even invented! But it was only until after the discovery of quantum mechanics and atomic energy levels that the mechanisms behind these unexplainable sources of microwaves were understood. Since then, astrophysical masers have been vital in theories regarding galactic structure and star formation. So let’s take a closer look at some natural astrophysical masers.

Star-forming regions

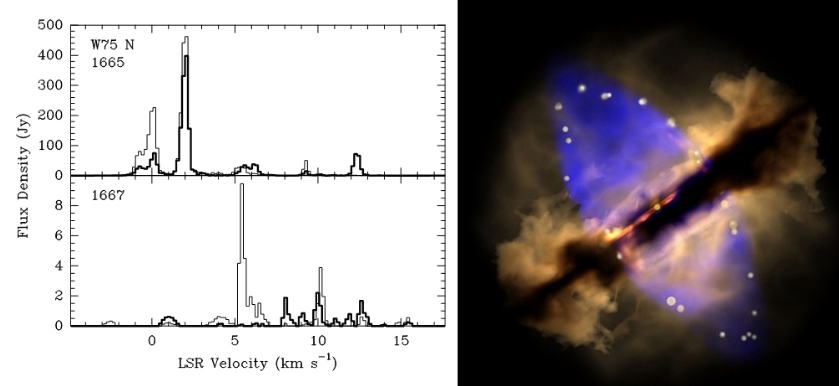

Stars form when denser regions in interstellar molecular clouds undergo gravitational collapse. In the beginning stages of stellar evolution, massive amounts of energy are generated. Parts of the molecular clouds nearer to the protostar are energized by it, resulting in population inversion and becoming masers. Star forming regions are known for OH, methanol, ammonia, and even water masers.

Credit: (Left) Fish & Reid (2007); (Right) Wolfgang Steffen, Instituto de Astronomía, UNAM

Circumstellar envelopes

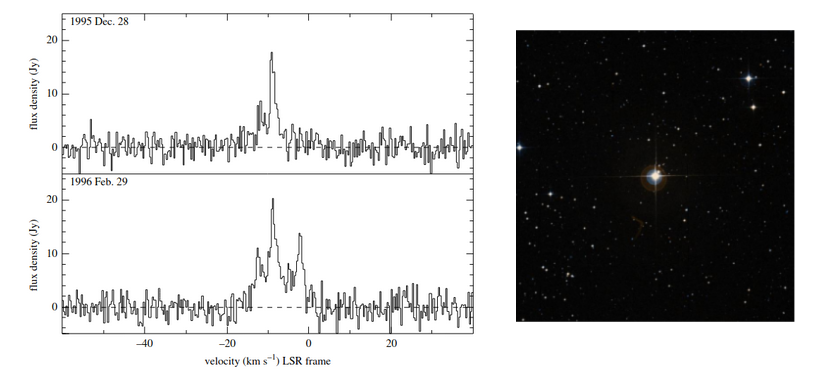

At the end of the life of a low mass star, it enters its red giant phase. The star becomes incredibly variable and starts to pulse. These pulsations and strong stellar winds cause massive amounts of the stellar atmosphere to swell into a surrounding structure not gravitationally bound to the core of the star. This structure is known as a circumstellar envelope (CSE). These CSEs, pumped by the red giant stars they surround, also become notable masers. The composition of the CSE is largely tied to the star and the stage of evolution the star is currently in. Earlier in the red giant phase, oxygen is more common in the CSE than carbon, resulting in a prevalence of oxygen-based maser species like SiO, H₂O and OH. As the star evolves and begins to nucleosynthesise carbon, the CSE also becomes more carbon rich, resulting in HCN and CO masers.

Credit: (Left) Thompson & Gray (1999); (Right) Dominic Ford, in-the-sky.org

Supernova Remnants

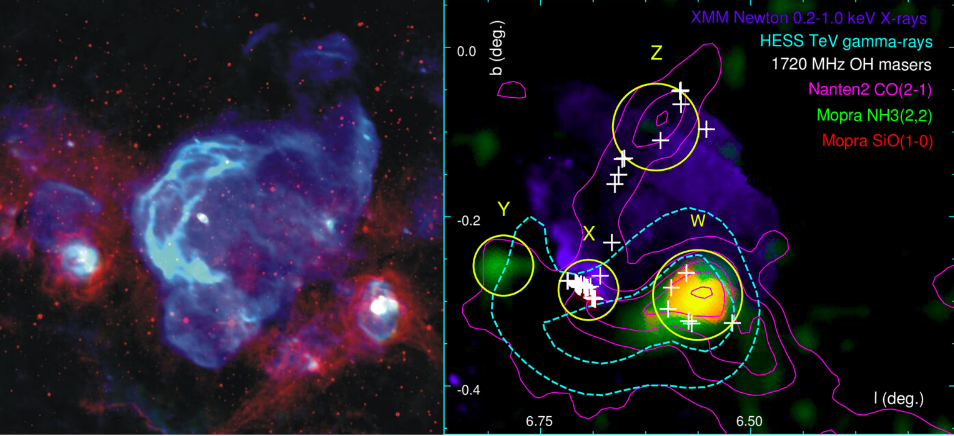

Supernova remnants (SNRs) are what remains of sufficiently massive stars when they have reached the end of their lives and explodes. Sometimes, supernova remnants interact with interstellar molecular clouds and a rare type of OH masing of 1720 MHz is observed. Unlike the OH masing (1665 MHz and 1667 Mhz) in star-forming regions, the one observed in SNRs require colder environments with less far-infrared radiation which cannot be found near young, hot stars.

Credit: (Left) Brogan et al, Legacy Astronomical Images; (Right) Maxted et al (2016)

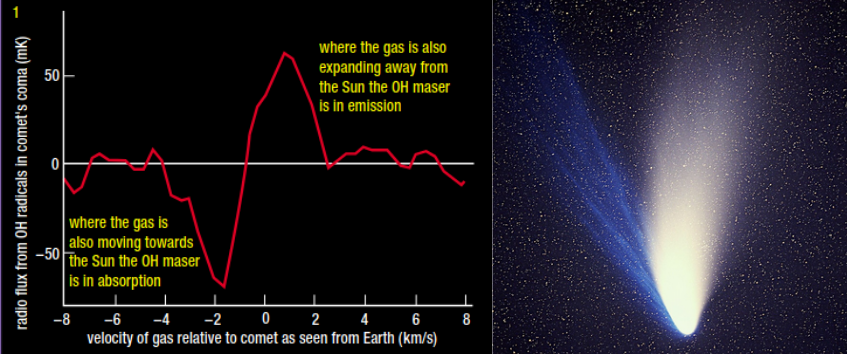

Comets

There are also masers closer to home. As comets approach the sun and the temperature increases, volatile substances on the comet sublimate and are blown away from the comet in a tail-like shape. This is known as outgassing. One of the molecules commonly outgassed is water, which, when exposed to solar radiation, dissociates into OH radicals. UV radiation from the sun also induces population inversion, resulting in a maser. Such masers are different than those above as the movement of the comet greatly affects the gas, in fact, when velocities are low, background masing frequencies are absorbed rather than amplified.

Credit: (Left) Richards & Spencer (1997); (Right) Erich Kolmhofer (Johannes-Kepler Observatory), Herbert Raab (Johannes-Kepler Observatory)

There are many, many more kinds of astrophysical masers. Given the many possible masing mediums and variations in environments in space, each is unique in its own way, lending us different insights into our universe. Microwaves continue to be an important source of information, giving us access into a universe that is invisible to us. More than that, could it also be a tool with which humanity can utilise to broadcast our existence? Astrophysical masers, though lacking in visual splendor, are pretty a-masing.

written by Chloe Lim 22 November 2025