The discovery

A neutrino with an estimated ~200 PeV* energy likely hit our planet in 2023. For a sense of the scale of this, if the neutrino’s rest mass were one second, its total energy would be about the age of the universe! Earth is constantly being bombarded by high-energy particles. The charged ones (mostly protons and nuclei) are what we usually call cosmic rays. Because cosmic rays are charged, magnetic fields scramble their paths; neutrinos travel straight, so they can point back to where they came from. Neutrinos aren’t cosmic rays in the strict sense, but they’re part of the same particle ‘weather’. They are often produced when cosmic rays crash into matter or light. Most are low-energy and harmless, like a drizzle we never notice. That constant bombardment is a kind of particle weather. If we could see all these particles, the sky would never be clear, and there would be constant rain from all points in the sky. This analogy is extremely apt, because when charged cosmic rays hit the atmosphere, they trigger cascades of secondary particles called air showers. When a charged ‘drop’ hits the atmosphere, it splinters into a shower; neutrinos usually slip through without making a splash. This article follows the neutrino side of that story.

*PeV stands for petaelectronvolt, which is 10¹⁵ electronvolts, an enormous energy unit for a subatomic particle

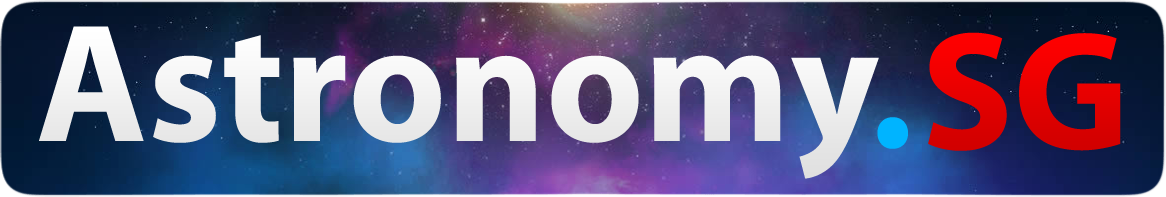

Figure 1: ARCA’s detectors are suspended deep inside the Mediterranean Sea. The muon travelled roughly horizontally, as seen, through the detectors, giving us high confidence that its source was a high-energy neutrino.

Rainfall, rainfall everywhere!

These nearly massless particles play an indispensable role in late-stage stellar evolution and have been key to how we’ve tested particle physics. However, most of them pass by like invisible drizzle. They are primarily produced through the weak interaction. Here, ‘weak’ doesn’t mean feeble; it refers to the weak force, one of the four fundamental forces. This force drives radioactive decay, including processes used in nuclear power.

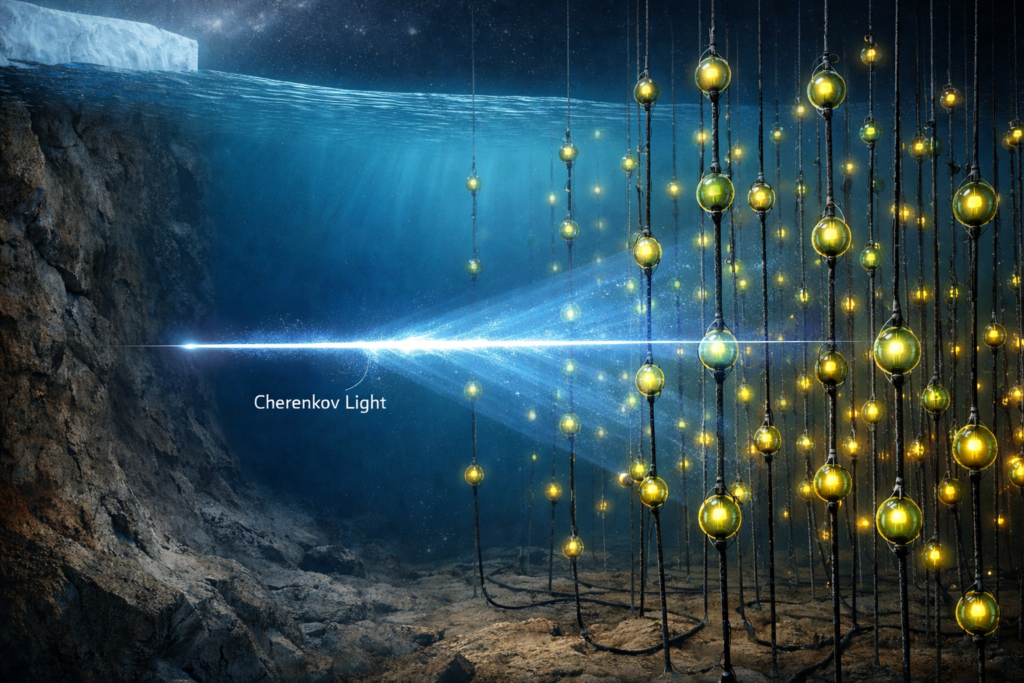

Figure 2: For a muon to be created from a neutrino, the latter must interact with a charged particle through the Weak force. Rock and water thus plentifully provide for charged particles for such an interaction to occur.

How many neutrinos reach Earth? Neutrinos have masses far smaller than the electron’s (exact values are still being pinned down). If you are familiar with the latter, you would know that there are already some very low-mass elementary particles. Given this extremely low mass, it is easy to intuitively expect that they are produced in extremely large quantities in energetic cosmic processes. The stellar fusion occurring in the Sun, for instance, is a large source of neutrinos due to its proximity to the Earth. Due to it, about 65 billion neutrinos are passing through each square centimetre of the Earth every second! However, most of these pass through the Earth as if nothing were there. This is because they interact only via the weak force (and gravity). It is said that to reliably stop a neutrino, a layer of lead about one light year thick is needed!

Figure 3: The Sun is the main source of neutrinos in our neighbourhood, and these are created in the energetic fusion reactions happening within the Sun’s core.

Seeing the invisible

Given that it is so difficult to observe neutrinos, how is it that we have observed them? For such a particle, there is only one reliable way to detect it, and that is sheer volume. By increasing the volume of the detection area, one has a greater chance that a neutrino will collide with it and give off light. Given the signal is so weak, background charged particles must be filtered away. It’s like trying to catch a few special raindrops in a storm of lookalikes. To do this, the setup is built deep underground or underwater so most charged-particle backgrounds are absorbed before reaching the detector. The medium can be any transparent, ideally dense material. A classic example of this is the Super-Kamiokande detector in Japan, which uses water as its detecting medium. It helped confirm the occurrence of neutrino oscillation, a long-suspected phenomenon that explained why fewer solar neutrinos were detected than expected. In our case, the neutrino detector is called ARCA, which is located 3.5km deep in the Mediterranean Sea and which uses seawater as its detection medium.

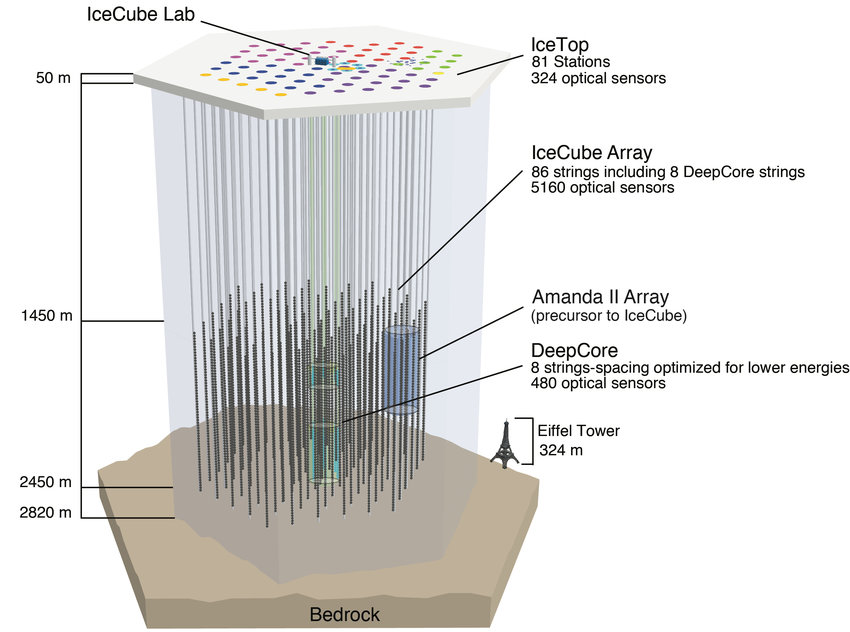

Figure 4: The IceCube observatory is similar in design to ARCA, except that it is embedded within clear Antarctic ice. Measurements done on this ice have showed that photons can travel for hundreds of meters without getting scattered, making it the ideal material to detect neutrinos. [1]

From drizzle to hail

Stellar fusion is but one among countless known mechanisms producing neutrinos. By and large, the spectrum of neutrinos that have been observed can be explained by these known mechanisms. A prominent one, for example, is the cosmic neutrino background. This consists of all the neutrinos that were generated during the Big Bang. This population likely has the highest density of all sources, but is extremely hard to detect. But once in a long while, the weather throws hail in the form of neutrinos so energetic that they are not easily explained by the usual sources. One such neutrino was inferred in 2023, when ~110 million triggers on ARCA’s detection lines yielded a candidate event with 28,086 hits. This wasn’t drizzle. It was a hailstone. The detection was so energetic that the photomultiplier tubes closest to the particle’s trajectory were saturated.

An important point to note here is that the particle detected was in fact not the neutrino itself, but a muon produced by it (and hence an indirect observation of a neutrino) – the streak the hailstone leaves behind. But how do we know that the source of this muon was a neutrino? How do we know that the muon itself was not the original particle, or that it was a cosmic proton or something else that created that muon? Firstly, muons are unstable and decay quickly. They are only created from energetic interactions between specific particles above certain energies. Hence, the original particle that travelled through space and crashed into the detector is very unlikely to have been a muon. Secondly, the muon detected travelled nearly horizontally through the detectors. This implies that the source particle must have travelled through rock and seawater to get there. Charged particles cannot do this as they get quickly absorbed by matter. Neutrinos are the only type of particles that can travel through so much of the Earth without stopping. Hence, neutrinos are the most plausible culprit.

Measuring an extreme energy

How energetic was it? The scientists inferred the neutrino’s energy by estimating the energy of the detected muon, which was estimated at 120 PeV. While this is hardly a tight bound, it lets us establish a strong bound for the neutrino’s energy, which comes to 220 PeV. In our weather metaphor, this is hail at cosmic scale. There are two leading mechanisms known for producing such high-energy neutrinos – cosmogenic neutrinos, where ultra-high-energy cosmic rays interact with the Cosmic Microwave Background/Extragalactic Background Light to produce them, or certain classes of extreme astrophysical sources (e.g., some AGN/blazars) that could produce neutrinos of such energies. However, the livetime of 335 days for which the ARCA detectors were active makes such a detection statistically unlikely for such a high-energy neutrino to be detected.

Figure 5: Optical detection module used by ARCA. Many thousands of these lie in suspension under the ocean, and are the detectors that catch the faint pulses of light released when the secondary particles are generated by neutrino-water interaction. [2]

Tracing the neutrino’s origin

The next obvious question becomes, what does this statistical tension imply? It says one of two things: either we got lucky, and it just happened to be the case that a high-energy neutrino from known mechanisms produced a detectable muon in ARCA, or there is an additional high-energy neutrino component beyond the well-measured population measured so far. It is important to note that a “new component” could still be standard physics, but just a population we have not seen clearly before.

One hailstone, not yet a climate shift

Researchers then searched for a source by reconstructing the muon’s trajectory, with which they could constrain the part of the sky where it came from. They identified a region in the constellation Monoceros, with right ascension and declination of 94.3° and -7.8° respectively, as the best-fit direction (with uncertainty) of the neutrino. They traced the hailstone’s direction back to the sky. The region was then searched for compelling sources of such high-energy neutrinos, but none were found that gave significant statistical confidence, with a reported tension of ~2.2σ (under certain assumptions). ~2.2σ corresponds to roughly one such event per ~70 years for that configuration. While this may sound significant enough to ring the alarm bells of a new source of neutrinos, scientists usually demand a much higher level of confidence, about 5σ or 1 in 3.5 million, to be confident about seeking a change in models. As it stands, this is seen as a fluctuation with room for exploration, not a call to change our understanding of neutrino physics. For now, it’s one hailstone – intriguing, but not yet a climate shift.

Figure 6: The region of the sky from which the neutrino originated was narrowed down to a ~1.5° radius sphere around the encircled portion.

written by Raviraj Talgeri 20 December 2025

Resources

[1] Image by IceCube Collaboration, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

[2] Image by KM3NeT Collaboration, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Illustrations in Figures 1 and 2 generated with ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.2), December 2025.