Betelgeuse is arguably one of the most iconic stars in the night sky. One of the brightest stars, visible from both hemispheres, is visibly reddish (though there are historical records that suggest that it was once yellow!) and also located in an iconic, easily identifiable constellation, it has managed to capture the attention of astronomers for centuries and has been the pioneer in many stellar astronomy developments. It was the first star (other than the sun), to be directly imaged and have its angular diameter directly measured. Now, it has returned to the spotlight yet again.

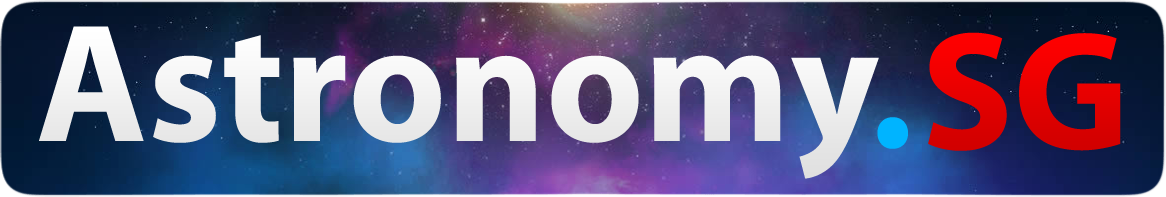

The recent surge of attention to Betelgeuse came with The Great Dimming in 2019, when the star’s brightness plummeted from a magnitude of 0.5 to 1.7, a whole threefold decrease in brightness! This led to speculations that the star would undergo an imminent supernova, which was very exciting — Betelgeuse is the closest red supergiant to Earth, a supernova would be bright enough to be visible even during the day. Telescopes were pointed at it, collecting as much information as possible. But alas, the star gradually returned to its usual brightness across the next few years. Turns out, it was merely an ejection of gas from the stellar surface, a “sneeze”. However, armed with a lot more data, astronomers were now able to shine a light on some of this red giant’s more peculiar features.

Image credit: NASA

Ever Changing

Betelgeuse is highly variable and have several distinct periods of variability, two of which is of peculiar interest: one that lasts for about 400 days and another that lasts for about 2100 days (or about 6 years). The shorter, 400 day period, is likely the fundamental mode (FM) of the star — essentially the lowest frequency that a pulsating star expands and contracts.

Why the 400 day period instead of the 6 year one? There are many incredibly technical reasons but chiefly, an FM of 6 years would require that Betelgeuse has a radius of a thousand solar radii, which Betelgeuse does not have. Secondly, it would also mean that Betelgeuse is fusing carbon into neon in its core and on its deathbed, astronomically speaking (only hundreds of years left before going supernova, instead of hundreds of thousands). The case for a 6 year FM is small. It is a lot more likely that the 6 year period is a Long Secondary Period (LSP), and a result of external factors, most popular and likely amongst them being: a companion star.

The case for a companion star

High Surface Velocity

Betelgeuse rotates at a speed of 5 km/s, incredibly fast for a cool evolved star like Betelgeuse. To put things into perspective, the sun has a surface velocity of 2 km/s. If we were to expand the sun into the size of Betelgeuse, it would rotate at 2 m/s, if we also increase the mass of the sun to that of Betelgeuse’s, the rotation would slow down further to 0.2 m/s. This is due to the conservation of angular momentum. Therefore, it is impossible for Betelgeuse to have such a high rotation speed if it were a single-star system like our sun.

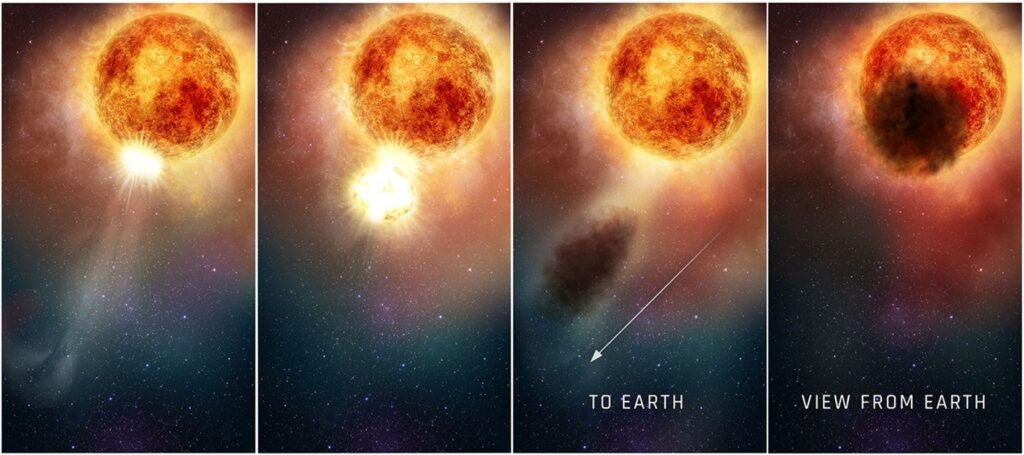

Image credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/E. O’Gorman/P. Kervella

A companion could explain this high rotation speed, as Betelgeuse would be able to gain angular momentum from it. It can also be the result of a binary merging or convective motions across the surface of the star which might look like rotation.

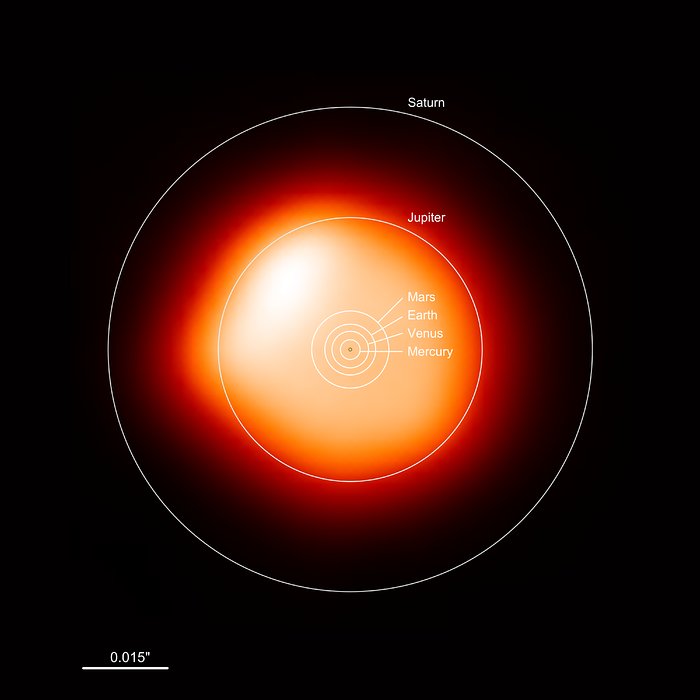

Lightcurve and Radial Velocity variations

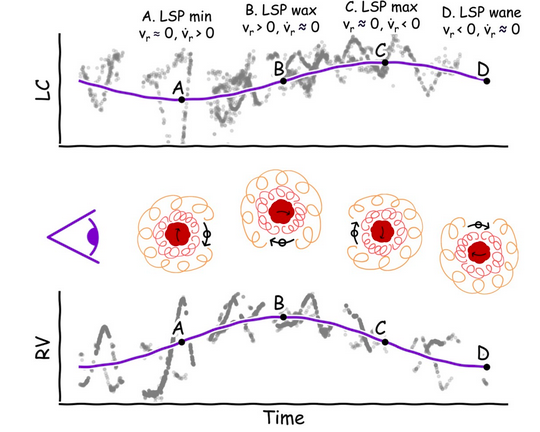

The 6 year period can also be observed when plotting Betelgeuse’s radial velocity (or velocity in the direction directly away from Earth). In other words, Betelgeuse appears to be “wobbling”, a tell-tale sign that there is another body, like a planet or another star, orbiting around it.

Credit: Goldberg et al (2024)

Minimum brightness seems to correspond to when Betelgeuse appears to begin moving away from the observer. This does contradict a popular binary model that postulates that the minimum brightness should happen as the companion passes in front of the star, when the star would appear to have no orbital RV.

The most likely explanation would be a companion whose close orbit around Betelgeuse affects the circumstellar matter in its vicinity, changing its opacity and density. It seemed that the bulk of circumstellar matter was about 180 degrees out of phase with the companion.

Image credit: Goldberg et al (2024)

Smoking gun

The case for a companion star was stronger than ever, and lacked only one thing: a direct observation and evidence. It would be difficult. The companion star would be small, no more than 1.5 solar mass, and optimistically, 4 orders of magnitude dimmer. Next to Betelgeuse, it will be hundreds of times smaller. Betelgeuse is also highly variable, its luminosity and temperature fluctuations would easily overwhelm any small variations caused by the companion star. As a result, despite being theorised to be a binary system for centuries, it has never been directly confirmed…

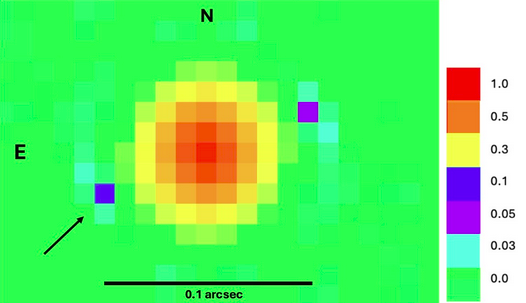

Until July 2025, Howell et al published possible direct imaging of this elusive companion star. Interestingly, it was done with an Earth-based telescope, Gemini North in Hawaii. It was accomplished using speckle imaging, an imaging technique where thousands of short exposure images are calibrated and compiled in order to minimise atmospheric distortions. Two speckle images were taken, one in February 2020 in the midst of the Great Dimming, and the second in December 2024. Predictions for the orbital path of the companion star had it eclipsed behind Betelgeuse in 2020, and it was indeed missing in the image. In December 2024, the star would be at maximum elongation (i.e. furthest angular separation) from Betelgeuse and would theoretically be visible. And it was!

Image credit: Howell et al (2025)

The image shows a star 52 mas (milliarcseconds) away from Betelgeuse, at an angle of 115 degrees, which agrees with predictions of the companion star.

The star was named Siwarha, Arabic for “her bracelet” as it orbits Betelgeuse, the “hand” of Orion. Based on the data that we have, it is likely that Siwarha formed at around the same time that Betelgeuse did, but it is a Young Stellar Object (YSO) that have not begun hydrogen fusion yet, whereas Betelgeuse has already evolved into a red supergiant due to its greater mass. Its future is not looking bright (or rather, it might be too bright), Siwarha’s close orbit to Betelgeuse would also mean that it might be cannibalized by Betelgeuse in the next 10 000 or so years.

Further solidifying the discovery of a companion star around Betelgeuse is a recent study published on 5 January 2026 in which eight years of spectroscopic data was analysed. It revealed curious behaviours in Betelgeuse’s outer atmosphere, like variability in absorption in the circumstellar atmosphere of Betelgeuse. Taking the orbital behaviour of Siwarha into account, it seems that immediately after transit (Siwarha passing in front of Betelgeuse), the circumstellar disk starts to dim, reaching a minimum brightness half a period later before gradually increasing in brightness.

Artwork: NASA, ESA, Elizabeth Wheatley (STScI); Science: Andrea Dupree (CfA)

So what is happening? The theory proposed goes as follows:

Siwarha is orbiting in the chromosphere or the “atmosphere” of Betelgeuse. It gravitationally focuses surrounding winds, creating a trailing tail or wake, like a boat through water. Denser gas would accumulate in this wake, blocking a portion of the light from Betelgeuse. The wake gradually expands, taking about 3 years (or half a period) to cover Betelgeuse’s entire surface. After, the collection of dense gas dilutes, so Betelgeuse gradually increases in brightness. The process then repeats as Siwarha passes across the same spot again.

Preferably, a second direct image should be taken of Siwarha. However, currently, it is eclipsed by Betelgeuse. The next window of opportunity to directly image it would be in 2027. But astronomers will have something to occupy their time until then. An LSP is not a trait unique to Betelgeuse, many red supergiants, like Antares and Arcturus have a long variability period that could also be explained by a yet undiscovered companion. This development opens new doors in stellar astronomy and research.

Written by Chloe Lim 17 January 2026

Resources:

Hasan, P. (2026). The Betelgeuse Enigma: The Betelbuddy Hypothesis. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2601.02012

Howell, S. B., Ciardi, D. R., Clark, C. A., Hope, D. A., Littlefield, C., & Furlan, E. (n.d.). The Probable Direct-imaging Detection of the Stellar Companion to Betelgeuse. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.15749

MacLeod, M., Blunt, S., De Rosa, R. J., Dupree, A. K., Granzer, T., Harper, G. M., Huang, C. D., Leiner, E. M., Loeb, A., Nielsen, E. L., Strassmeier, K. G., Wang, J. J., & Weber, M. (2024). Radial velocity and astrometric evidence for a close companion to Betelgeuse. The Astrophysical Journal, 978(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ad93c8

Goldberg, J. A., Joyce, M., & Molnár, L. (2024). A Buddy for Betelgeuse: Binarity as the Origin of the Long Secondary Period in α Orionis. The Astrophysical Journal, 977(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ad87f4

Dupree, A. K., Cristofari, P., I., MacLeod, M., & Kravchenko, K. (2026). Betelgeuse: Detection of the expanding wake of the Companion Star. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2601.00470