One of the greatest achievements of mankind happened so long ago that a lot of us (and possibly our parents) weren’t even alive to witness it, the Moon Landings. Our only real knowledge of the Apollo program might only be from a mere paragraph in a history textbook, random encounters of conspiracy theorists claiming that it was a hoax, or through some “who was the first man to walk on the moon?” type trivia question. How exactly did they put a man (or a dozen) on the Moon?

To put it briefly, the Apollo Missions aimed to fly a three-man crew into orbit around the Moon, then send two men down onto the surface for up to 35h while the third remained in orbit, after that, a rendezvous in lunar orbit, and finally, flying all three men back to Earth. The entire mission would last about 8-10 days, but the Apollo Spacecraft could support the crew for up to 14 days.

To put it lengthily, well:

The Vehicle

There are two main vehicles in each Apollo mission: The Saturn launch vehicle and the Apollo spacecraft.

Image credits: heroicrelics

Saturn Launch Vehicle

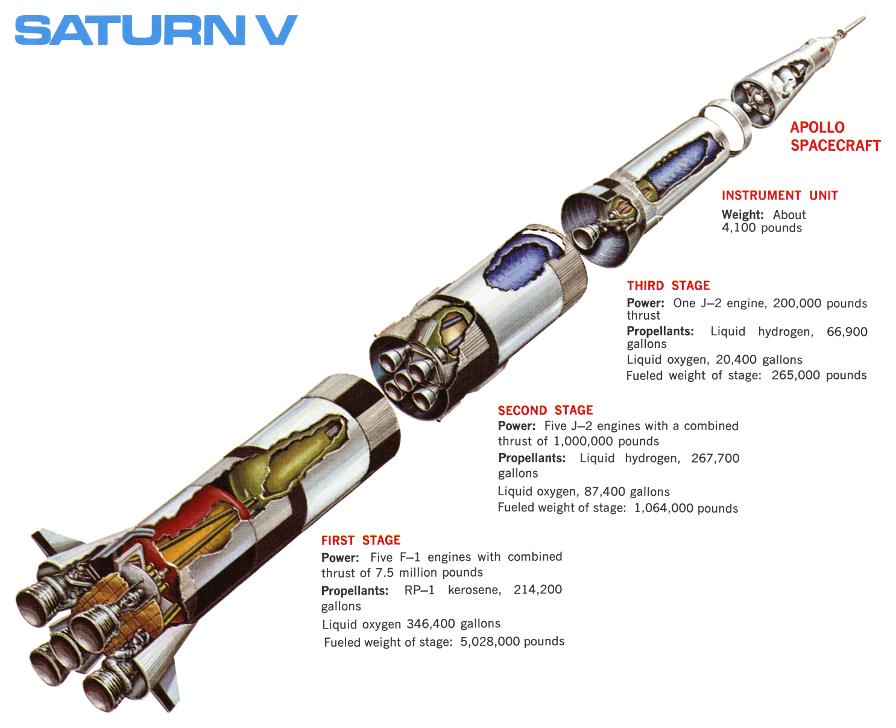

The launch vehicle used in the Apollo missions came from a family of launch vehicles originally under the jurisdiction of the US Department of Defence, intended for use in ballistic missile research, only transferring to NASA in 1960. There are three members in this family: Saturn I, Saturn IB, and Saturn V. Saturn V is the launch vehicle designed specifically for the Apollo Program. Despite debuting all the way back in 1967, it remains to this day one of the most powerful launch vehicles ever made, capable of generating 41 million newtons across three stages.

It is an absolute behemoth, standing at a little over 70m and weighing 2.8 million kg fully fueled! It has three stages and an instrumentation unit for guidance, control, tracking and monitoring. We’ll get back to the functions of the three stages when we go into a step-by-step breakdown of a manned Apollo mission.

Apollo spacecraft

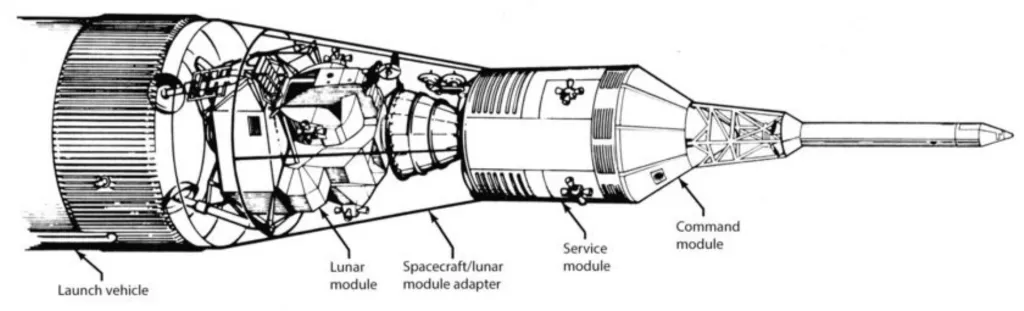

Sitting on top of the launch vehicle, this is the payload of the Apollo Missions. It houses the astronauts, and everything they would need for the entire mission. It has five notable components: the launch escape system, the command module, the service module, the lunar module, and the spacecraft-lunar module adapter.

Credit: NASA

The launch-escape system serves as an emergency escape for the astronauts should anything go wrong during initial lift-off, taking them safely away from the rest of the spacecraft and launch vehicle. The spacecraft-lunar module adapter encloses the lunar module in an aerodynamic conical shape and also serves as a connection between the spacecraft and launch vehicle. They are jettisoned early in the mission once they have served their purpose.

The remaining three modules are more important and make up the main spacecraft.

Command Module

The command module (CM) is the control centre for the spacecraft, living and working quarters of the crew, and where all the important equipment is stored. Aside from when two of the crew descend onto the moon on the Lunar Module (LM), the crew will not leave the CM for the entire mission. It will also be the only part that returns to Earth.

Image credit: NASM, Jim Preston

The CM has to protect the astronauts from some of the most extremes of environments. During the journey there, temperatures can range from a freezing -173.3°C on the side away from the sun to a boiling 137.778°C when in direct sunlight. On top of that, during take-off, friction could heat the spacecraft up to 600°C. But even that pales in comparison to the intense heat of re-entry, at 2760°C, most metals would melt. Yet within the crew compartment, temperatures are controlled at a comfortable 21°C to 27°C. This is possible through:

- an insulation layer sandwiched between the outer and inner shells of the CM

- a slow rotation of the spacecraft when traveling through space

- a boost protective cover made of fibreglass and covered with cork to protect from the heat of take-off, jettisoned with the launch escape system at about 90m in the air

- a phenolic epoxy resin that chars and melts away under the intense re-entry heat, dissipating the heat before it reaches the interior.

The CM has three compartments, the forward, crew and aft.

Image credit: NASA

The crew compartment, as the name suggests, contains the crew. When inside, the astronauts are usually in their respective chairs, called couches, but they can leave and move around if needed. There are windows and mirrors used for photography, observation and to help navigate during docking and rendezvous maneuvers. Along the interior walls are equipment bays and cupboards containing everything that the crew would need for their mission, like food, waste management, toolkits, medical kits, guidance and navigation electronics, and suits and helmets.

In the forward compartment, everything needed for Earth landing is kept: parachutes, recovery antennas, and beacon lights. In the aft compartment are engines, fuel, oxidizer, helium and water tanks, and other instruments. The CM lands aft down, so within the aft compartment is the impact attenuation system, designed to absorb the majority of the energy during reentry.

For most of the mission, the CM will be connected to the service module (SM), collectively, they’re referred to as the CSM.

Service Module

Image credits: NASA

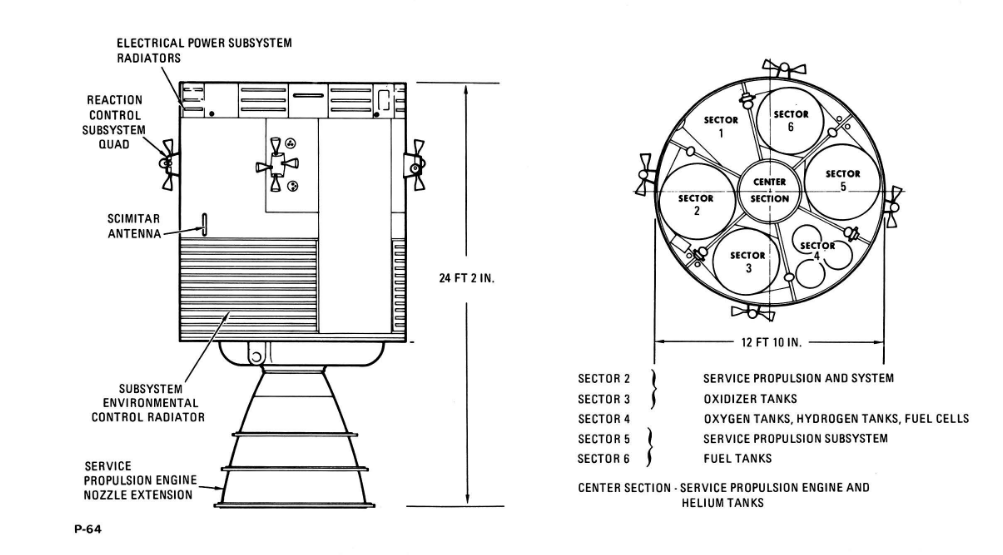

The service module (SM) contains the main spacecraft systems and equipment, and consumables. It is a cylindrical structure connected to a cone-like propulsion engine. The propulsion engine performs course corrections, puts the spacecraft into orbit around the Moon, and sends the spacecraft back to Earth.

Within the main structure are cryogenic hydrogen, helium, and oxygen tanks, fuel cells that provide electrical power to the spacecraft, and systems for environmental control, communication, reaction control, and any other scientific equipment that might be needed on the mission.

Lunar Module

The Lunar Module (LM) is designed to bring two of the astronauts down onto the moon and back up into the orbiting CSM. It can support two crew members for 48 hours. It has two main components: The ascent stage and the descend stage.

Image credit: NASA

The ascent stage lies on top. It houses the crew compartment and equipment for ascending off the lunar surface into lunar orbit. It is essentially a control centre for the lunar module, with displays and controls for landing, takeoff and docking back with the CSM. Despite having no seats (only armrests), the ascent stage is equipped with provisions for sleeping, eating and waste management.

The descent stage consists of the descent engine and accompanying propellants, the landing gear, scientific equipment to be used on the Moon, and extra oxygen, water and helium tanks. It will also double as a launching platform and remain on the moon.

The Journey

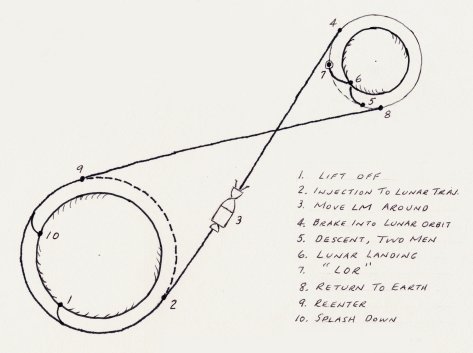

The astronauts did not take-off straight into a moon-ward trajectory, land on the moon, then take-off from the lunar surface into a direct flight home. While sounding relatively easy, this method — known as Direct Ascent — is a technological Everest. To accomplish this, a launch vehicle that can generate 178 million newtons is needed (compared to Saturn V’s 41 million newtons). It is simply unfeasible. Instead, the Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous is used.

Credit: WIkimedia

The Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous involves sending the spacecraft into lunar orbit, then landing only a small lunar module onto the surface. The module would then ascend back into lunar orbit to rendezvous with the spacecraft and travel back to Earth. This way, the mass of what eventually lands and takes-off on the Moon is minimised, needing a lot less thrust, and a lot less propellant. Therefore, this method greatly reduces the technological challenges present.

The entire lunar mission is, expectedly, very complex. Here, we’ll try to cover the bare-bones of the journey taken by the Apollo crew.

Lift-off: Stage 1 of Saturn V fires, lifting the entire space vehicle (all 3 million or so kilograms), off the launch pad and into the sky. Despite burning a total of 2.5 min, it achieves a velocity of about 8700 km/h, after which stage 1 is jettisoned. Stage 2 fires for about 6 min, increasing the velocity to about 24 000 km/h, before also being jettisoned. Stage 3 takes over, burning for about 2 min to increase the velocity to about 26 000 km/h and bring the spacecraft into Earth’s orbit.

Heading towards the Moon: The spacecraft will remain in Earth orbit for final system checks before stage 3 is ignited again to put the spacecraft into a Moon-ward trajectory known as the ‘free-return’ trajectory. If nothing is done to put the spacecraft in Lunar-orbit, the spacecraft will slingshot around the Moon and return to Earth. After about 5.5 min of burning, the velocity is now about 39 000 km/h.

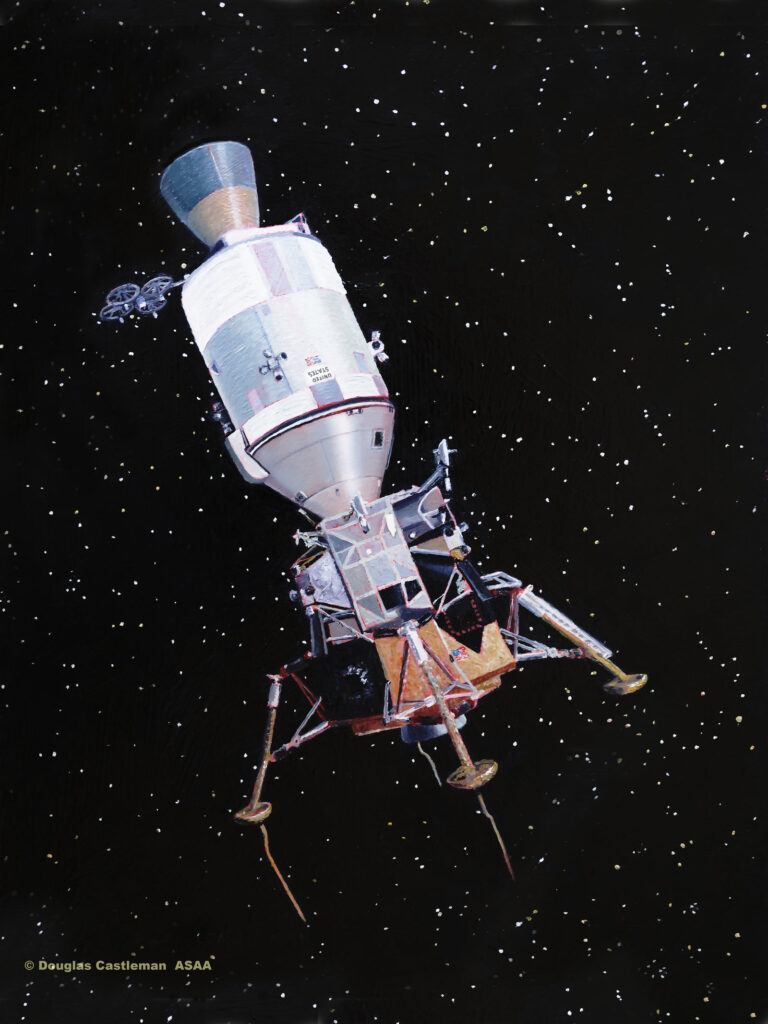

Reconfiguration: Next, the spacecraft-lunar module adapter opens to expose the LM, which separates from the CSM. The CSM then does a 180° turn and docks with the LM. Stage 3 is also jettisoned during this phase. Once the docking is complete, the astronauts can settle down for a long journey to the Moon.

Image credit: Douglas Castleman

Coast: Throughout this 2 to 3 day journey, the spacecraft is set to a slow roll so that the sun does not shine directly on any side for too long. The velocity of the spacecraft will also start to decrease due to Earth’s gravitational pull, but will eventually start increasing again when they draw closer to the Moon.

Entering Lunar orbit: When it’s time to enter Lunar orbit, the SM propulsion engine fires, slowing the spacecraft down from about 9000 km/h to 5800 km/h. The LM is checked and the two preselected crew transfer into the LM.

Moonwalk: The LM then descends onto the lunar surface. Time spent on the Moon varies from mission to mission, with the shortest being Apollo 11 at 2h 31min and Apollo 17 the longest at 22h 2min. During lunar stays, extravehicular activities are usually divided over two periods with a sleep in between.

Rendezvous in Lunar orbit: As mentioned above, only the ascent stage of the LM leaves the Moon. It takes off into lunar orbit and rendezvous with the CSM. Equipment and samples are transferred from the LM into the CM and equipment no longer needed is transferred from the CM to the LM. The LM is then jettisoned and the SM propulsion engine fires to put the CSM into a trajectory back to Earth.

Coast 2.0: The journey back to Earth is the longest stage of the entire mission, taking anywhere from 80 to 110 hours. The spacecraft starts from a velocity of about 8800 km/h and decelerates due to the Moon’s gravitational pull but eventually starts to accelerate due to Earth. When it enters the atmosphere, the velocity would be at around 40 000 km/h. The SM is jettisoned shortly before reentry into the atmosphere.

Re-entry: The CM is oriented flat end forward for reentry. Friction with the Earth’s atmosphere generates massive amounts of heat. Yet even though temperatures outside reach upwards of 2000°C, the cabin interior remains a cool 26°C. At an altitude of about 3200 m, parachutes are deployed. Remaining propellant is burned, recovery beacons are activated and antennas are also deployed for communication. And thus ends a successful Apollo Mission.

Image credit: NASA

A brief retrospective

On 25 May 1961, when JFK announced the plan to put a man on the Moon by the end of the decade, America had only managed to put a man in space for a mere 15 minutes. Yet, only 8 years later, on 20 July 1969, Apollo 11 successfully landed on the Moon and Neil Armstrong became the first man ever to walk on another celestial body. At its peak, more than 20 000 companies and 370 000 individuals were directly involved in the Apollo Program. It also required hundreds of billions of dollars to fund. While we marvel at the technological feat it is, we must remember that it is an exception and not the rule. It remains one of the most expensive and extensive programs ever undertaken. Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that after Apollo 17 in 1972, Moon landings were put on hold. It simply was not a sustainable endeavour.

For those of us disheartened to have been born too late to witness the Apollo Missions, fret not! The Artemis project, Apollo’s successor, is set to have its first crewed test flight in February 2026! While it is only a test flight and they will not land on the lunar surface, it shows that we might be on the verge of another era of Moon landings.

Written by Chloe Lim 6 December 2025